“How hard could it be?” thought Silicon Valley veteran Rob Trice as he considered launching a specialist food and agriculture fund.

The answer, he now admits more than a decade later: “Harder than other areas I have invested in, like social media. Tweeting is not like eating.”

Trice has spent the past ten years exploring that reality through Better Food Ventures, an organisation he set up to invest in early‑stage companies bringing IT solutions to some of farming’s biggest problems. Its portfolio so far includes Afresh, Breedr, and Milk Moovement.

ATN sat down with Trice and Better Food Ventures’ managing partner Michael Rose to discuss applying the Silicon Valley playbook to agriculture, why agtech “is not the darling of the dance,” and how Trump‑era tariffs continue to ripple through US farming.

ATN: Where did Better Food Ventures come from?

Rob Trice (RT): Michael and I first met around 15 years ago back in the telecom days. I’d been in venture capital since 2000. It was exciting, but by the time people started talking about 5G networks, I just didn’t have it in me.

I’d started thinking about where Silicon Valley would next direct its digitisation efforts, and I saw my wife — who runs a cattle ranch — struggling to use Square at a farmers’ market. I thought: “This is 5–10% of the world’s economy. How hard could it be to digitise food and agriculture?”

I launched two organisations and Michael quickly joined me. One is The Mixing Bowl, which connects food and ag innovators for thought and action leadership. The other is Better Food Ventures, which invests in companies applying information technology across the food and ag value chain to make a positive impact.

We define positive impact not necessarily as social impact — though we want to do good — but as the power of profitability.

ATN: What kind of companies are you looking for?

RT: We had a thesis as classic early‑stage investors to focus only on digital technologies — companies capable of earning SaaS‑style revenue multiples.We don’t do CPG. We try to avoid anything too hardware‑intensive. We don’t do retail. We don’t do farm operations. Even biologicals, chemicals and inputs we stay away from. Fundamentally, we’re digital monkeys.

ATN: Without an agriculture background, how do you know which problems need solving?

RT: We spend a lot of time listening to the market. And there’s a track record: digital ag companies have exited for $300–400m. If you look at the multiples, you can still make good money.

Michael Rose (MR): Like any good business, we talk to the customer. We spend huge amounts of time with ranchers, farmers, orchard owners — the people who actually use these tools. You have to understand their needs and challenges.

RT: And you have to bring a seasoned investor’s understanding of what is a real pain point. What is a vitamin — and what is a painkiller? Don’t get duped by technology looking for a market.

ATN: Is the Silicon Valley playbook suitable for agriculture?

RT: The venture model can be applied selectively. But I don’t think Silicon Valley investors — aside from impact investors — are about to change how they deploy capital.

MR: And when people say “the Silicon Valley model,” they’re usually thinking about social media. This is not social media. These are not consumers downloading an app and creating instant proliferation.

Venture investing existed long before social media — in hardware, infrastructure, routers, switches, B2B. Ag looks more like that era.

ATN: Agtech funding keeps sliding. What do you make of that?

RT: I’m not surprised. The market is — for lack of a more polite term — constipated. There are 150 incubators, accelerators and venture support organisations pushing more deals through the funnel.

But investors also need exits or company failures. And failures create scar tissue that makes investors hesitant. We don’t have many winners — but we’ve had some high‑profile strikeouts.

To be fair, it’s not just agrifoodtech. Fintech is down. CPG is down. AI is the belle of the ball, sucking oxygen away from alternative funding.

ATN: Is the sweet spot somewhere between AI and ag?

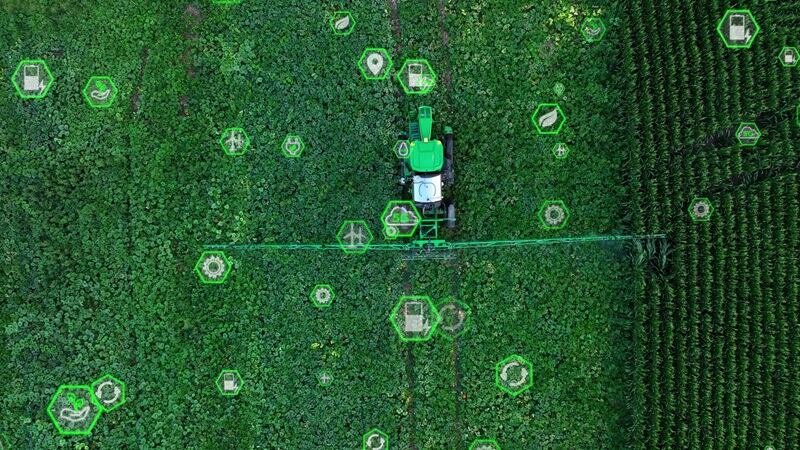

RT: Absolutely. The message we’re pushing is that for AI to work in food and agriculture, we need good data. But a lot of farms still don’t have digitised data.

MR: The trend we see is physical AI — the “big iron” players like Kubota and John Deere taking equipment into the next generation.

ATN: As an investor in AI companies, does it matter who owns the data?

RT: I think there’s an assumption — written or unwritten — that the farmer owns the data. The real question is whether the farmer will allow that data to be used for a stated purpose.

Usually, if the farmer understands who is using the data and why, they’re okay. There’s a lot of talk about paying farmers for data, but I don’t think we’re there yet.

Michael and I are working with others on a nonprofit called COSSAF — the Collaboratory for Open Software & Systems for Ag & Food. Terrible name, but we’re trying to fill some gaps. One big one is data ownership.

One solution we’re developing is SADIE — Smart Asynchronous Data in Escrow. Like money in escrow, farmers don’t have to hand over raw data to customers. Instead, they can attest: “These avocados are organic — if you doubt it, you can verify through the escrowed data.”That prevents misuse because you’re providing answers, not datasets.

ATN: Is US economic policy affecting ag investment?

RT: Yes. Many farms aren’t making money. Here in California, tariffs have hurt the almond market. They’ve also hit corn and soy. When farmers’ margins drop, they simply don’t buy as many things.