Many have cast 2025 as a transition year or shakeout period. Venture funding into agtech fell to one of its leanest levels in a decade, pushing start-ups to prioritise clear customer demand and viable unit economics. Yet deployment of AI‑driven, climate‑focused and automated technologies continues to deepen, potentially laying the groundwork for a more disciplined phase of growth.

A new paper from Ankit Chandra, director and lecturer in agtech entrepreneurship, and Ishani Lal, economic analyst at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, finds that 2025 revealed deep, systemic pressures across the global agtech sector.

Chandra told AgTechNavigator that “tight margins, slow adoption, and cautious investors” will continue into 2026, but rebound signs are clear in water and energy efficiency, AI decision‑support, evidence‑backed biologicals, and low‑CAPEX automation and sensing.

Meanwhile, high‑infrastructure categories such as vertical farming and insect protein will remain challenged unless they “fundamentally change” their economics or energy sources.

Problem sectors: CEA, insects, digital platforms and sensors

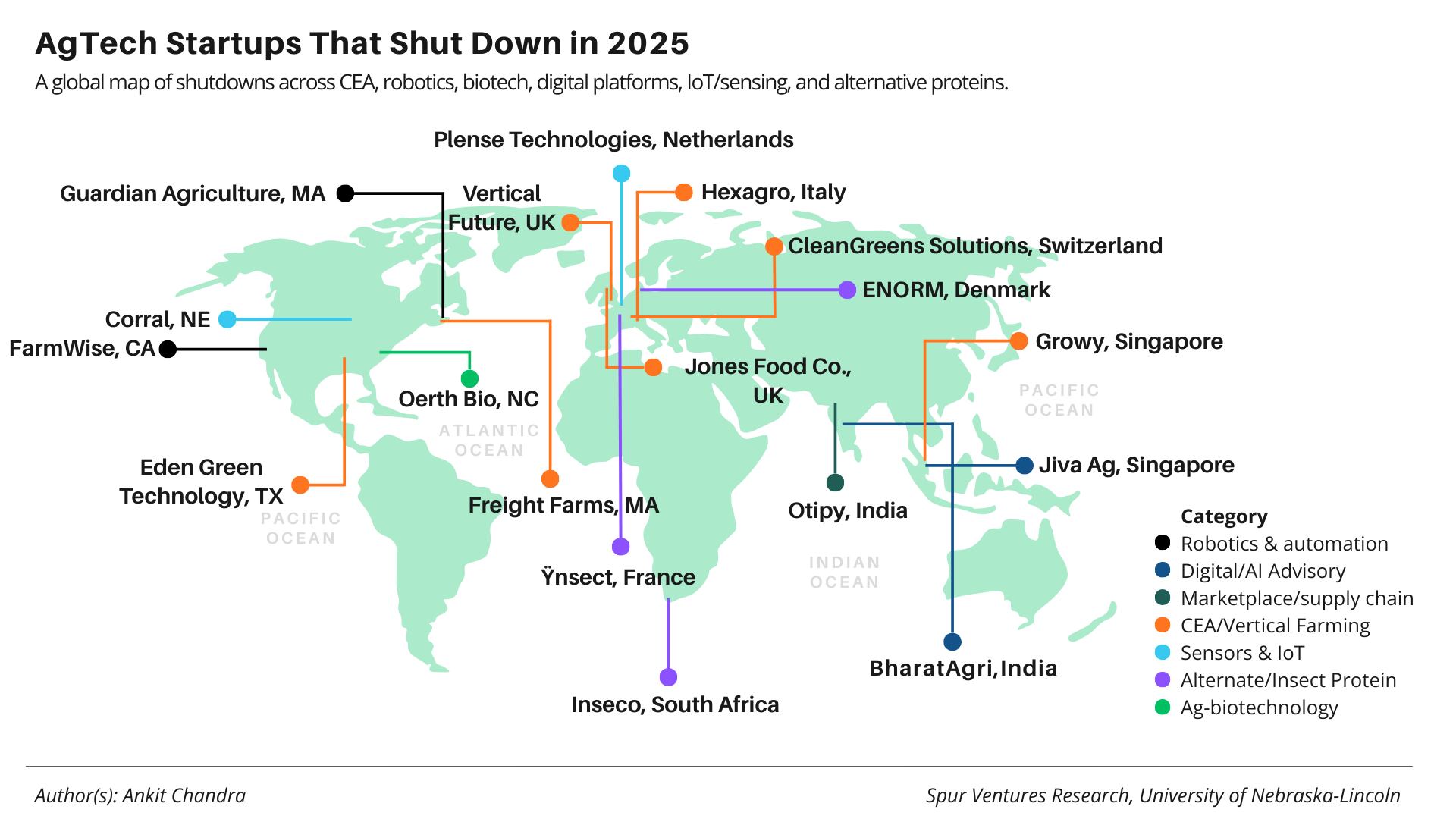

Chandra’s dataset identifies the highest 2025 shutdown rates in: CEA / vertical farming (6); insect & alternative protein (3); digital advisory / marketplaces (3); sensors / IoT: (3); robotics & automation (2); and ag‑biotech/deep‑tech (1).

Despite their differences, the drivers were common: high operating and energy costs, long or uncertain paybacks, slow farmer adoption, fragile unit economics, and difficulty scaling revenue fast enough to keep up with burn rate.

“Even companies with strong technical results struggled when the economics didn’t work,” Chandra said.

Failures were geographically broad. North America and Europe registered more closures because they host more capital‑intensive ventures, while South Asia saw digital and supply‑chain platforms – including Jiva Ag, Otipy and BharatAgri – struggle with high acquisition costs and low willingness to pay. “No ecosystem was safe,” Chandra stressed, noting that the constraints were structural, not regional.

Capital intensity shaped time‑to‑failure

The analysis shows a stark pattern: high‑capital ventures died slowly, while low‑capital ventures died fast.

Large CEA facilities and insect‑protein companies – some having raised $100M+ or, in cases like Ÿnsect, several hundred million – survived 5–15 years through repeated fundraising without ever achieving viable unit economics. Low‑CAPEX digital and sensor firms (examples are BharatAgri, Jiva Ag, Plense Technologies) had only 2-6‑year runways before adoption bottlenecks caught up with them.

“Capital can extend the runway but does not fix underlying economics,” Chandra concluded.

What drove shutdowns

Across cases, Chandra identifies several dominant failure modes:

- Farmer adoption constraints: thin margins, seasonal cash flow, risk aversion

- High operating/energy costs

- Long or uncertain payback

- Integration complexity in robotics, drones, automation and digital platforms

- Technology‑field mismatches

- Over‑broad value‑chain ambitions, especially digital start-ups trying to internalise logistics

- Premature scaling and vertical integration in CEA and insect protein

Half the shutdowns in the dataset were directly tied to cost and adoption constraints. Macroeconomic forces – higher interest rates, supply‑chain disruptions, energy price volatility and climate‑driven farm risk – accelerated failures by exposing weak economics.

Founder lessons for 2026: evidence, economics, partners

Chandra offers three blunt lessons for teams building in 2026: design for farm economics and adoption first. Deliver fast, predictable ROI; avoid solutions requiring significant behaviour change amoung users; integrate into existing workflows.

Avoid high‑CAPEX models unless unit economics are proven early. Infrastructure‑heavy systems are too fragile in today’s capital environment.

Don’t rebuild entire value chains. Partner locally with co‑ops, processors, credit providers and retailers to accelerate trust, distribution and adoption.

For investors and accelerators, he advises: no SaaS‑style expectations for hardware/biologicals; validate adoption earlier; fund field‑scale integration; demand credible payback; align milestones to agricultural seasons; support modular and service‑based models; avoid ‘megaproject’ logic in CEA and insect protein.

Where resilience is emerging

Despite 2025’s turbulence, Chandra believes several subsectors show strong resilience signals:

- AI‑enabled agronomic advisory & analytics (low CAPEX, scalable revenue, fast workflow integration when evidence is strong)

- Embedded agfintech (credit, insurance and payment models tied directly to existing farm transactions)

- Evidence‑driven biologicals & nutrients (rigorous replicated data, transparency, integration with machinery/precision tools)

- Post‑harvest storage, cold chain and quality control (universal pain points; modular and energy‑efficient solutions win)

- Water & energy‑linked systems (solar pumping, electrification, storage; immediate and measurable cost savings)

Bridging the‘valley of death’

Chandra argues that most failed start-ups proved the science but not the adoption. The bridge to commercial scale lies in multi‑region field validation, risk‑sharing models, and integration into existing supply chains rather than building new ones. “These strategies directly counter the cost-adoption mismatch patterns we observed,” he said, “where heavy capital requirements and high adoption friction ultimately led to failure.”

He calls on universities, incubators and policymakers to expand multi‑season testbeds, demonstration farms, field‑scale trials, blended‑finance mechanisms, loan guarantees and infrastructure improvements – from rural power to cold chain – to lower adoption friction and derisk scaling.

“Ecosystem interventions like blended capital, on-farm testing platforms, public–private partnerships, and service-based models help mitigate the same structural pressures that shaped the 2025 shutdowns,” he concluded.

“By reducing capital intensity, spreading risk, and supporting evidence-driven deployment, such support mechanisms can soften the structural bottlenecks that caused many of the 2025 failures and create a clearer path from early innovation to commercial scale.”

Read the paper:

https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biosysengpres/83/ – Ankit Chandra & Ishani Lal, University of Nebraska–Lincoln (UNL Digital Commons).