French insect-farming pioneer Ÿnsect has entered judicial liquidation after failing to secure the financing needed to sustain its large-scale operations. Despite raising over €600 million and being hailed as a leader in insect protein, its capital-intensive, highly automated model proved too costly to scale. Attempts to restructure and adopt a leaner model were not enough, and in December 2025, a French court ordered the shutdown and sale of its assets. While its flagship mealworm facility near Dole will close, a smaller pilot site will continue under a new venture focused on producing fertilisers from insect by-products. An announcement is expected at the beginning of 2026.

The move begs the question: is the future of insect farming rooted in feed and fertiliser rather than human food ingredients? Fertiliser from insect frass is gaining traction for its soil health benefits and circularity appeal, and the Keprea pivot suggests short-term revenue opportunities may lie here. But others caution against reading Ÿnsect’s collapse as proof of a sector-wide pivot.

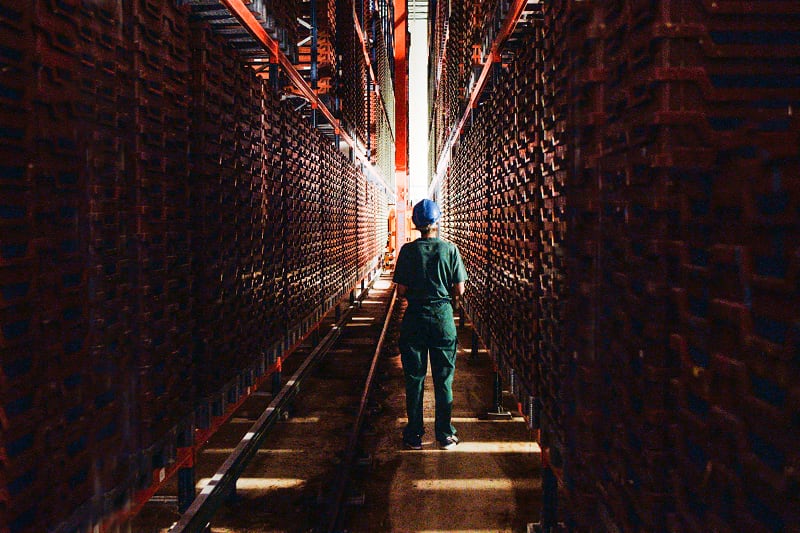

The cost of scaling too fast

Dr Geoffrey Knott, chair and novel foods lead at the UK Edible Insect Association (UKEIA), told AgTechNavigator: “Ÿnsect’s liquidation is disappointing. They were one of the most visible pioneers in the sector, and any high-profile exit is a loss. But it also reflects the challenges of scaling too fast, too early. Their model relied on very large, capital-intensive facilities at a time when the market – and the economics – were not yet mature enough to sustain that level of expansion.

“There are lessons in Ÿnsect’s story about scalability, capital discipline, and aligning growth pace with market readiness. But it shouldn’t be mistaken for sector-wide weakness.”

Knott argues that both protein and frass have roles in a mature insect farming ecosystem: “It’s too early to claim that fertiliser-focused approaches are the validated path. They may simply be more aligned with shorter-term revenue opportunities under current market conditions. What matters is building economically resilient models that match scale to demand, operate within regional cost realities, and grow as the wider market evolves.”

Knott believes Ÿnsect’s shift shouldn’t be read as proof that protein-for-feed models are inherently high-risk or unviable. “What it really reflects is how difficult it is to compete with global feed commodities that operate at massive scale, with very low production costs, often in regions with warmer climates and fewer regulatory constraints,” he said. “Europe has higher energy and labour costs, cooler temperatures, and tighter regulations – all of which push up the cost base for large insect facilities. That makes timing and scale especially critical.”

The UK’s ‘measured approach’ offers a contrast

Knott remains bullish on the UK sector, which he says has taken a “measured, evidence-led” approach: “Companies here are proving viability on smaller systems first, strengthening technology, and expanding stepwise as real demand increases. It’s a more grounded trajectory, and it’s one reason investor interest in the UK remains steady.”

With regulators modernising frameworks and government backing for food system resilience, he is confident the UK will emerge as one of Europe’s most promising hubs for edible insect innovation.

“We expect UK companies to benefit from clearer, more proportionate pathways than those facing many of our EU counterparts,” he said. Based on recent study published in the journal Foods, the UK has more edible insect businesses and start-ups than any other European country.

A high-profile fall

Ÿnsect’s collapse is a cautionary tale about scaling too aggressively in a nascent market. It doesn’t spell the end for insects as food – but it does underline the need for disciplined growth, diversified revenue streams, and models that reflect regional economics. Fertiliser may offer a near-term lifeline, but the long-term vision still includes insect-based ingredients on the human plate.