The Danforth Technology Company-founded biotech start-up Spearhead Bio received a $305,000 grant from the US National Science Foundation (NSF) to develop corn varieties that are resistant to a range of agricultural challenges.

Founded earlier this year, Spearhead Bio was born out of the center’s research on transposable elements, primarily on soybeans, Keith Slotkin, principal investigator for the Danforth Technology Company, told AgTechNavigator. Transposable elements are DNA sequences that “have learned through evolution to insert themselves into our genome and into plant genomes,” he explained.

Transposable elements are “somewhat similar to a virus, but they cannot leave the cell,” but instead can move within genes, leading to DNA mutations in future generations, he added. These “jumping genes” represent 50% of the human genome and 80% of the DNA in corn, UC Davis reported.

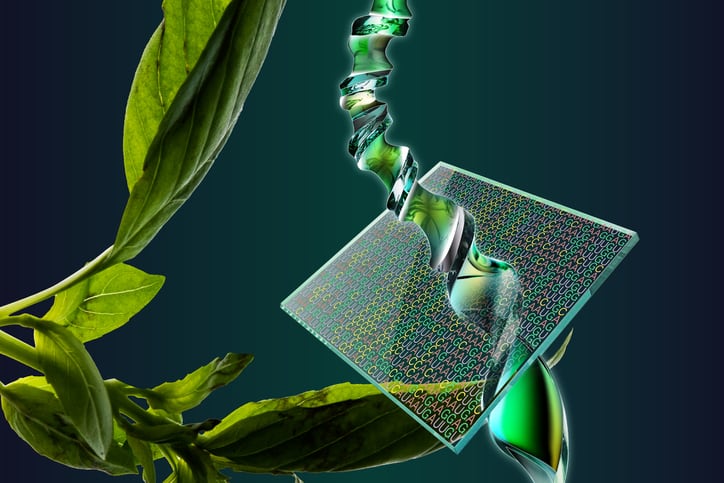

Spearhead Bio developed a proprietary technology called Transposase Assisted Homology Independent Targeted Insertion (TAHITI) that inserts genes into transgenic and non-transgenic crops, which can create genetic traits for crop benefits like disease resistance. Gene-editing technique CRISPR/Cas is effective at cutting the genome, but adding custom DNA can be tricky, Slotkin explained.

“The way we like to put it is that CRISPR-Cas created this amazing set of molecular scissors, and the transposable elements are really complementary to that. They create essentially molecular glue. And together with the scissors and glue, you can start to really edit and rearrange a plant genome the way you want it — that is particularly valuable as we try to improve crop plants,” Slotkin elaborated.

Instead of releasing products itself, the start-up is working with companies to “help them realize their product goals and use their scalability,” Slotkin explained.

“The current pipeline has been estimated to be roughly 16 years and $150 million to produce a new trait. We can do this much more efficiently,” he emphasized.

The regulatory burden facing gene-edited crops

Agriculture companies create new crop varieties through transgenic editing, leading to some regulatory challenges, Slotkin explained. Europe and Africa require authorization for importing genetically modified crops, he added.

“We have a system right now where the crops that have been improved by the major companies are transgenic. They carry foreign sequences and that creates a large amount of what we call regulatory burden. You have to do a bunch of regulatory science, and it is a slow process. They cannot get them to market quickly, and then you have to keep that crop separate because there are countries and entire continents right now that are not accepting those crops,” Slotkin added.